CHIMERAS, 2022-2024

Lamarck always speaks of environments (milieux) in the plural, and by this he explicitly means fluids like water, air and light. When Lamarck wants to designate the set of actions exerted on the living being from outside, that is to say, what we today call the environment, he never says environment, but always “influencing circumstances”.

Georges Canguillem, from The Living Being and its Environment

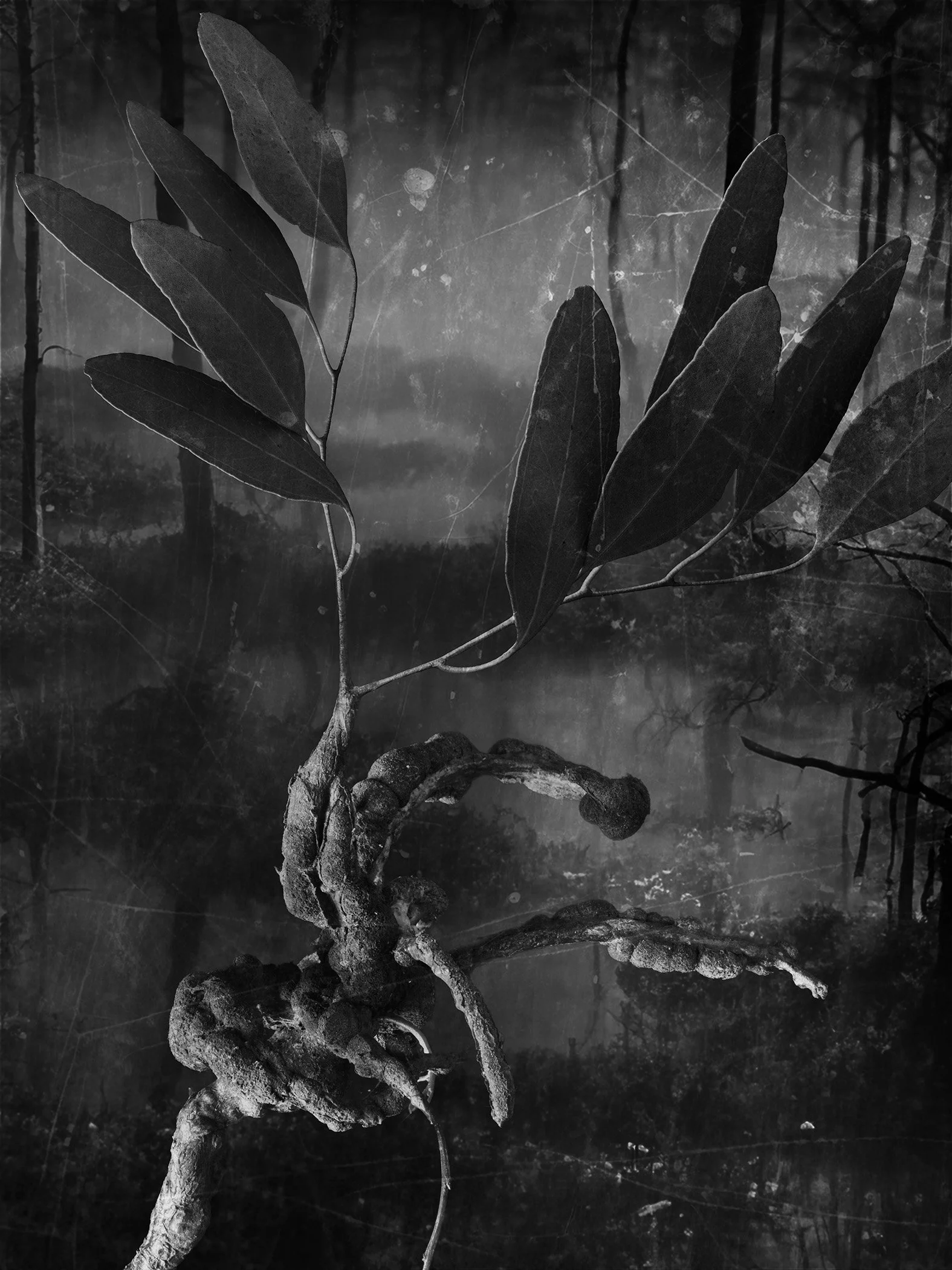

Chimeras (2022-24) is a series of botanical works made in the age of climate change, or as some scientists now call it, the Pyrocene. The works depict existent individual botanical species ‘hybridised’ with other species; manually grafted, these new species cannot exist: studio constructs, rather than genetic outcomes.

Within Homer’s Illiad, the “chimera” originally depicted “in the fore part a lion, in the hinder a serpent, and in the midst a goat, breathing forth in terrible wise the might of blazing fire”. In biology, however, a chimera designates an organism of different genetic tissues; in the field of genetics, chimera describes interspecies hybrids.

The series employs techniques borrowed from nineteenth century photography and dioramas. Louis Daguerre, a progenitor of early technical photographic processes - the daguerreotype - was originally a set designer for the Paris Opera, creating the first dioramas in 1812. While dioramas were originally conceived as ‘entertainments’ including moving screens and lighting techniques borrowed from theatre, to “produce an imitation of reality intended to create the most perfect replication of reality” (Puppe) the diorama eventually became a museum display, ideally suited for recreating zoological scenes and idyllic and exotic habitats, often extinct or endangered, and mostly colonised. The State Library of Victoria’s building once housed The National Museum and its collection of now dismantled dioramas: childhood memories.

In the same year that Daguerre’s diorama burnt down, he invented the daguerreotype: the three-dimensional became reduced to a single plane. Rather than the elaborate trompe l’oeil assemblages of dioramas, twentieth century cinematic visual devices, such as rear projection and green screens have been used to construct the series’ scenography. Scratched and solvent-altered 4x5 film negatives have also become a ‘filter’ between the image and the image’s plane: a return to the successive screens of Daguerre’s original dioramas.

The hybridisation of a begonia coccinea with a brugmansia suaveolens is impossible. However, within the photogravures, they become plausible organisms. Yet they are created - grafted - with temporary wire and string, putty and glue, becoming closer to taxonomy than Adolphe Braun’s nineteenth century botanical arrangements.

Elements of nineteenth century portraiture photography, and moreover twentieth century botanical photography (e.g. Karl Blossfeldt, Albert Renger-Patzsch, Adolphe Braun, and Robert Mapplethorpe) have also been referenced. Equally, references from early nineteenth century botanical/zoological illustration (e.g. Robert Thornton’s Temple of Flora, the illustrated volumes of Ernst Haeckel, Ferdinand Bauer) and science-fiction films (Lars von Trier’s, Melancolia, Douglas Trumble’s Silent Running) appear alongside those from art history.

Explicit in the growing environmental crisis, the series depicts these new chimeras in landscapes of fires, caves, wasted forests, and smoke-laden canyons and jungles, as if these landscapes bore these new genetics. While the works are atemporal, each work suggests potential forms of extreme environmental effects, and the subsequent genetic alteration of its organisms.

This work was assisted with a 2023 State Library of Victoria Creative Fellowship and printed at Baldessin Studio.

The work is dedicated to the memory of Patricia Hubicki (née Ward), my mother.